Bum rap | Encounter with Jesus, Jewish advocate transforms homeless man

— by Lori Arnold, Christian Examiner Newspapers

By the time Rufus Hannah was sprinting face first into stacked milk crates for $5 in beer money at the hands of young filmmakers recording the stunt for pleasure, dignity was no longer his friend.

The last remaining shreds of it probably evaporated the night teenagers sprayed him in the face with a fire extinguisher while he was trying to sleep in the upstairs doorway of a La Mesa office building.

Earlier chunks of his dignity frayed away even before that episode when a knife was thrust against his throat while a stranger rifled through Hannah’s pockets for whatever change he still had or one of the various times when beat officers kicked him awake in a rain storm, telling him to move on to another city.

Barry Soper, the landlord of a 61-unit condominium development in San Carlos, owned a piece of Hannah’s dignity as well after he barked at the homeless man as he popped out of a Dumpster at his housing complex— the same place where Hannah or his friend defecated from alcohol abuse a day earlier.

A disheveled Hannah tried to explain he was looking for cans and was a veteran.

“I don’t care if you are a veterinarian,” Soper screamed at the sorry spectacle before him. “I need you to get out of here.”

Rage burning inside of him, but too broken and drunk to do anything but comply, Hannah and his homeless compadre, Donnie Brennan, scuffled off to the next Dumpster.

“I was a sloppy drunk,” Hannah said, an addiction he earned earnestly from an alcoholic mom who, despite her Baptist roots, drank throughout her pregnancy and kept the legacy going by filling his baby bottle with beer.

Pleased that his booming voice—accentuated with an intimidating East Coast air—thwarted a major conflict, Soper headed back toward his complex office, but not before stopping to share his war story with Orlando Hawkins, a neighbor who lived across the street from the complex. Hawkins, an intimidating presence who loved to sit on the porch and watch the world go by, listened as Soper relived his triumphant exchange with the homeless bums.

Ninety-year-old Hawkins was not impressed.

“He started telling me, ‘Jesus wouldn’t like you,’” Soper, a Jew, recalled. “‘You have to change your ways and you have to hire them.’ It offended him.”

Pragmatic at heart, Soper figured he’d appease his friend, certain the pair would never follow through.

“So I offered them a job, and Mr. Hawkins is like, ‘Yes!’

Fresh from verbally accosting the pair, Soper tracked down Rufus and Brennan at another Dumpster and offered them work.

“Be here at 10 a.m. sober and you have a job,” Soper commanded.

Hannah was skeptical of Soper’s seemingly schizophrenic behavior, but vowed to show up the next day.

“I didn’t know what was going on with him,” Hannah said.

But he was pragmatic, too, and needed every cent for alcohol.

• • • •

For several years Hannah survived in his own asphalt Bermuda triangle along the Navajo Road corridor where the cities of San Diego, El Cajon and La Mesa abut. He and his buddy, Brennan, looked out for each other on the streets, developing a bond forged from the camaraderie of being homeless veterans; grown-up versions of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, but instead of scouring the countryside for wild adventures the pair took to commercial Dumpsters seeking cast-off food, discarded cigarettes, and aluminum cans that funded their daily alcohol binges.

Hannah had learned to pour every drop of alcohol he found —type didn’t matter—into a single container, which he squirreled away for later in the day.

“It didn’t matter what it was because I needed a drink,” Hannah said.

Sometimes he woke in the middle of night to take a few swigs to stave off the alcohol seizures that would erupt when he went too long without any in his system.

Each night he would look for a secluded spot where he hoped to sleep without harassment. He would loiter in an area for as long as he could before officers shooed him along to one of the adjacent cities.

• • • •

Soper, satisfied he had done his part to keep his Christian friend Hawkins, happy, went about his business that afternoon; Rufus and Brennan delegated happily into his past.

“I drive in the next day to my shop and to my amazement—a little disappointment probably—there they were,” Soper said of Hannah and Brennan. Stunned that they took him up on his offer, Soper sent his daughter off to a fast food restaurant to buy the pair some breakfast and coffee while he tried to come up with an actual job for them.

When they had finished their hot meal, Soper had them work on some fencing, a project that kept them busy for about eight weeks.

“They were like craftsmen,” the property owner said of his temporary employees. “I got to know them more as human beings than as homeless people. And I got to like them—except for Rufus. We really never liked each other for a long, long period of time.

“Donnie was almost like a salesperson. He’d put his arm around me; call me his “guardian angel,’ ‘my hero.’ I loved that. Who doesn’t like to get their egos stroked?”

But Hannah was still gruff and standoffish.

“I didn’t trust Barry,” he said. “I had grown that way after living on the streets. I just didn’t trust anybody.”

• • • •

On the top of his distrust list was Hannah himself. At 16, he opted out of a squirrel-hunting trip in his native Georgia with his father and brother. Instead, a neighborhood friend took his place. The teen, the son of a pastor, never returned; he was accidentally shot and killed on the trip by Hannah’s father after the boys migrated into the line of fire.

“(His dad) was never criminally charged, but emotionally he died that day,” Soper said. “Rufus had a lot of guilt about it, thinking that if he had gone on the hunting trip maybe things would have changed.”

In the ensuing years, Hannah’s dependency on alcohol increased, ending his marriage and leading to the estrangement of his son and daughter. Causing a ruckus in his hometown, Hannah enlisted in the Army, but broke his arm during boot camp. He was medically discharged before completing basic training.

He entered another relationship that produced two more sons and more broken bridges. Along the way a fifth child was born, but alcohol continued its wet rope around his neck. Eventually he landed in San Diego, where he met an unlikely advocate in Soper.

• • • •

After the fence project was complete, Hannah and Brennan went back to their routine on the streets.

“It was hard work,” Hannah said of the fence project. “We worked full days.”

Occasionally they would pool their money together with another homeless friend so they could rent a cheap motel room for the weekend. They would buy clean clothes at the thrift store, take showers and watch TV, safe from the elements for several days.

But more often than not, their days were spent in parks or along the streets trying to be just invisible enough not to draw attention to themselves, but without losing their humanity.

But even invisibility and humanity can be sold for the right price and Hannah and Brennan did so. The results were a series of videos called Bumfights in which the pair did drunken stunts for quick bucks to feed the buzz that fueled the pranks that made money for several enterprising teenagers.

“At the time, if I was recycling during the day, cannin,’ if I made $8 or $10 that was a great day. So $5 sounded good to me,” Hannah said.

In one exchange, Hannah beat his buddy so badly he shattered Brennan’s leg requiring metal rod to be implanted to hold his ankle to the limb. Brennan agreed to have the word Bumfights tattooed on his forehead; Hannah was less radical, inking the Bumfights letters just below each knuckle.

“They really violated his civil rights,” Soper said. “It kind of dehumanized these poor guys.”

According to the National Coalition for the Homeless, nearly 86,000 degrading videos of homeless people were posted on YouTube in just one month last year, the news agency AFP reported.

• • • •

Concerned for their safety, Soper contacted a Santa Ana law firm, but before the attorneys or investigators from the district attorney’s office could interview Hannah or Brennan, the filmmakers took the bumfighters to Las Vegas where they filmed more stunts and kept them below the radar. A month later, Hannah called the man he couldn’t trust to come rescue him. Soper was there by the afternoon. The next day he was putting them up in a motel.

Not convinced his kindness was leading to change, Soper said he decided to try some tough love.

“Instead of taking Rufus back to the motel I took him to a mortuary and I made a deal,” the businessman said. “I said to Rufus I’ll either buy you a casket today or you get into the program. No more motel. It is no longer an option.”

But Hannah needed to be sober for three days before he could enter the VA’s rehab program. On the third day Hannah was struggling against his own will. Brennan and Soper tied him up with bedsheets to keep him from drinking. The next day, weighing just 110 pounds, Hannah entered the substance abuse program.

“I was drinking a lot,” he said, usually consuming nearly two gallons of beer or .750 liters of vodka a day.

• • • •

Between meetings, counseling and pacing the floors, Hannah spent a great deal of time reflecting on his past. He remembered jogging with his then 6-year-old daughter in preparation for boot camp and how he promised to take her to her first day of school, only to break that promise to report for duty. Only to get hurt. Only to get discharged. Only to begin the descent into unbridled intoxication.

“I was having a hard time detoxing and I was layin’ there one night in my bunk and at the foot of my bed, I saw my daughter,” Hannah said, his voice cracking as each word emerged from his lips detached, but accented by an anguished breath released deep from a dark crater in his soul. His wet eye lashes framing clear blue eyes.

“It’s like she’s reaching her hand out and I was looking at her and it seemed like her face faded into the face of Jesus. I thought, ‘oh my gosh,’ I sat up on the side of the bed and put my face in my hands and it’s like God put his hand on my right hand and said, ‘You know what Rufus? You know, your kids mean more to you (than alcohol).’ So I decided right then, this is it. I gotta face it.”

• • • •

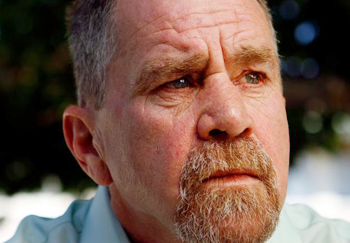

After his conversion to Christianity, and with eight years of sobriety, Hannah now works for Soper at one of his complexes. He’s reconciled with his children and married the mother of two of his boys. He volunteers on homeless issues and once again went before the camera, this time for a training video for law enforcement on how to treat the homeless with dignity.

This fall, Hannah and Soper released the memoir, “The Bum Deal: An Unlikely Journey from Hopeless to Humanitarian,” which details their improbable relationship. In 2008 Hannah was presented with a civil rights award from the California Association of Human Relations Organizations.

“There were five or six recipients in the whole state of California,” Soper said. “There were doctors and lawyers, then there was Rufus Hannah from Swainsboro, Ga., who hardly finished high school, never graduated from high school and there he was getting this major award. It was incredible. It made me feel so proud of him, so far he came.”

• • • •

Hannah is grateful for how far he has come, but his heart still aches for his pal Brennan, who still roams the streets thanks to the lure of his addiction.

“I miss Donnie a lot,” in tone that rings of compassion, not pity. “The last time I seen him, he was pretty messed up. He hugged me. He was crying.”

The first line of acknowledgments in his book is a tribute to that bond.

“Rufus Hannah wishes to acknowledge his best friend, Donnie Brennan. May he be safe.”

Editor’s note: This story was written in 2011, after the release of their book “A Bum Deal.” Sadly, Rufus Hannah was killed in a car crash in October 2017 in Georgia, where he moved to be with family. He remained sober until the time of his death.